Senator John McCain has died. Brain cancer. That sucks.

Unfortunately, albeit predictably, his death has sparked arguments about how to honor political adversaries. On the one side, there’s “he’s always been a war-mongering dick, so stop kissing his ass because he died.” On the other side, there’s “he fought for what he thought was right from Vietnam to Trump’s America, his service to country is admirable in this day and age.” Or…

https://twitter.com/stephaniemarya/status/1033814964203606021

That he was no hero to himself was what made John McCain the hero America actually needed. https://t.co/SPufW8u1u3

— The New Yorker (@NewYorker) July 22, 2017

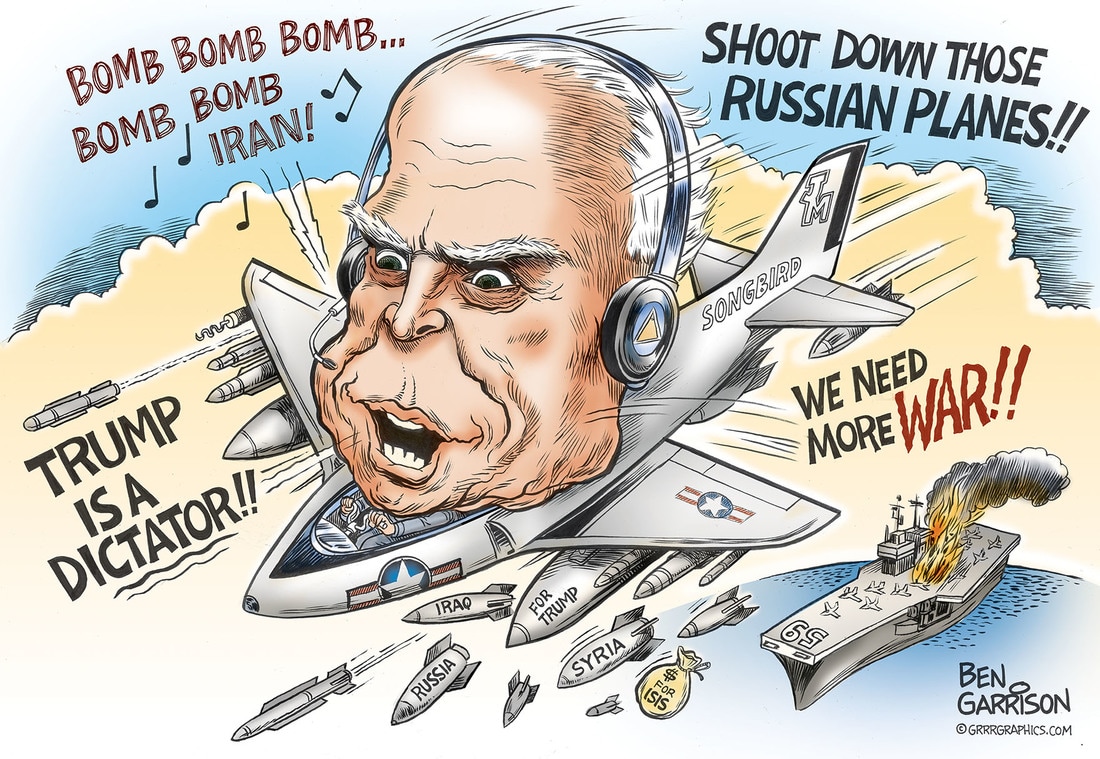

Although personally if I were to choose a side here, I’d be on the side of those willing to say the same thing about a person while he’s alive as in death. (As in, McCain willingly dropped bombs on civilians in Vietnam, was full of himself enough to run for President multiple times, gave us reality show politicians like Palin on the national stage and never saw a potential problem that WWIII couldn’t solve.) But a man died. That’s not usually a celebration in the press. More than any other recent death however, McCain’s demise brought out press coverage fitting of our times.

The New Yorker, as an example of the fawning mainstream media coverage, used his death and funeral as the last masterpiece chess maneuver of a dying politician to rebuke our sitting President. We put events like this into context by understanding them thru our preconceived narratives. In this case, McCain’s death was easily used as an example of the “Resistance” to our current administration. McCain knew how to manipulate his press coverage more than most politicians. His “straight talk Express” was fawned over by national networks from the New York Times to NBC News. This media helped to create and solidify McCain’s national narrative – as a “maverick”, a “war hero”, that rare politician to put country over party. The media helped to birth that personal narrative during his life – and then used that narrative to illuminate him in death.

Partisan identity

Americans are defined more today than ever before by our partisanship. We are not only polarized as political adversaries, but we are polarized and separated from each other when it comes to our social identities. Our social media feeds are most likely from similar political perspectives. Our social circles of friends, family, coworkers, neighbors and acquaintances are more likely to be from similar social and political backgrounds than ever before. One result of this social sorting is that partisanship has become more aligned with our social identity than ever before. We identify ourselves as partisans and then justify our positions based on our in group.

To many of those in the mainstream media, McCain signified some fantasy ideal of what cross partisanship should look like – putting country over party, service over self, straight talk over talking points. To many on the left, McCain signified war hawks, tax cuts, GOP establishment. As Trump and his supporters took over the GOP, the right derided McCain as a liberal, anti-Trump, weak-willed, Washington elitist. In other words, depending on the group you belonged to, you viewed McCain as liberal or conservative, everything that’s right with the right – or everything that’s wrong with it and as the last bastion of decency or an old partisan hack.

Simply put, our identities shape our worldview. Our worldview shapes the narratives thru which we seek to understand the world. When we seek to understand a new piece of information (say, a politician passing away), we attempt to put that information in the correct context. Our preconceived narratives do that for us. They allow us to make sense of the world – categorize it, understand it and explain it to others. It allows us, in this case, to use McCain’s death as part of the “resistance” (like the New Yorker), as a reminder of his leading role in the death and destruction of war (like many on the left) or as a Republican Senator elitist getting in the way of making America great (well, Trump supporters I guess).

Partisanship lives on

Our hyper partisanship today is based less on policy differences and more on social group dynamics. McCain, after all, was a dependable vote for conservative policies throughout his career. Our group identity as conservatives or as liberals are often less dependent on which policies are actually pursued, but instead on which group wins and loses. When our group wins, we feel pride. When our group loses, we feel shame and embarrassment.

McCain was the GOP nominee for President in 2008. They lost. Bigly. GOP partisans felt shame and embarrassment after their defeat in 2008 – to Barack Hussein Obama nonetheless. Another defeat for the presidency in ’12 left many in the GOP partisan base frustrated and ready for someone to bring back ‘winning’ to their group. Trump gave his GOP base something to be proud of, a channel to take their frustrations out on the out-group (“Lock her up!”etc), and a feeling of superiority over their opponents by winning. Trump’s ascendancy only emboldened his in-group supporters to further shun the ‘loser’ McCain.

McCain was the GOP nominee for President in 2008. They lost. Bigly. GOP partisans felt shame and embarrassment after their defeat in 2008 – to Barack Hussein Obama nonetheless. Another defeat for the presidency in ’12 left many in the GOP partisan base frustrated and ready for someone to bring back ‘winning’ to their group. Trump gave his GOP base something to be proud of, a channel to take their frustrations out on the out-group (“Lock her up!”etc), and a feeling of superiority over their opponents by winning. Trump’s ascendancy only emboldened his in-group supporters to further shun the ‘loser’ McCain.

Why does it matter?

So McCain passed away. Trump supporters don’t like him. Media love him. Leftists hate him, but some Democrats embrace him because they buy into the media narrative. Why does it matter?

Maybe it doesn’t matter. Maybe we shouldn’t read too much into the public reactions to a dead politician. Perhaps these reactions are unique to John McCain and not indicative of anything else. This is simply the latest in the never-ending line of media stories about our broken politics.

This story will be forgotten in a few weeks. The Senate is holding hearings for a new Supreme Court nominee. We are two months from the midterm elections. Then a litany of Democratic candidates will be running for President in 2020.

Even if we leave the tired debate about McCain’s funeral in the past, however, we will continue to debate incessantly over our political identity. That’s why this story matters. Look at what you truly believe: is it yours’ or your groups’ belief?